Project Mini Rack

Homelab Homelab / ˈhoʊm.læb / noun A personal IT environment where individuals can experiment, learn and test various technologies. A server (or multipl...

I’ve had an itch lately to do something with AES encryption in Powershell. I’ve tossed around the idea of building a password manager in Powershell, but I get so focused on the little details that I lose sight of the fact that Microsoft pretty much has that covered.

I’ve used ConvertTo/From-SecureString quite a bit for string management in scripts and I’ve even gone as far as creating a small module that allows me to save a credential using DPAPI encryption to an environmental variable for recall later. I have yet to do anything with AES encryption however. I have some scratch sheets saved regarding a more robust password manager module, but nothing has really come of it yet.

Two things happened recently to change some of this: I found myself with a need to encrypt some strings locally and save them to a file, and a coworker went down the rabbit hole of protecting PS credential objects with AES encryption. What follows is the story of ProtectString: A Powershell Module.

There are a lot of good articles out there on how to save Powershell credentials securely for use in scripts. Heck, I wrote one. For the sake of this post though let’s go over, specifically, the use of AES encryption for saving Powershell Credentials.

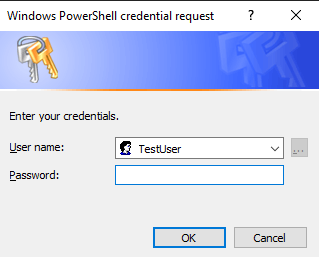

SecureString objects in Powershell are protected by Microsoft’s DPAPI encryption. Here’s the Wikipedia Page on DPAPI. Essentially the unique encryption key is derived from the user running it on the system they’re on. If a different user of the same computer tried to decrypt it using DPAPI it would fail. Move the DPAPI encrypted cipher text to another machine and try to decrypt it and it will fail as well. Not very portable, but it’s very convenient on the system you’re on. Using the Get-Credential cmdlet will yield a pop-up window where you can securely supply the password.

Get-Credential TestUser

UserName Password

-------- --------

TestUser System.Security.SecureString

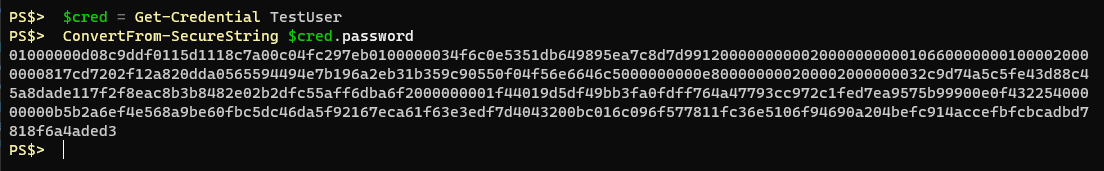

Using the Get-Credential cmdlet or the Read-Host cmdlet with the -AsSecureString parameter will net you a property that shows as a System.Security.SecureString object. If you were to convert from that SecureString object you would be left with cipher text:

Now, you could save this text to a file, and then read the text from a file later and convert it to a SecureString object and go about your business, but as I explained earlier it’s not portable because of the way DPAPI encryption works.

Consider the following:

# Make a new byte array of 32 bytes

$Key = New-Object System.Byte[] 32

# Randomize each byte value using the .NET random number generator

[Security.Cryptography.RNGCryptoServiceProvider]::Create().GetBytes($Key)

# Get the text you want to protect

$Secret = Read-Host -AsSecureString

# Convert it from a SecureString object to cipher text using our AES 256-bit key

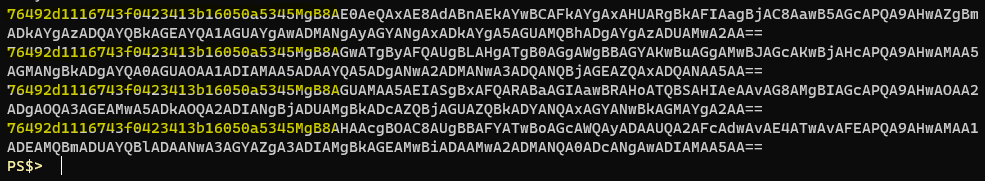

$AESText = ConvertFrom-SecureString $Secret -Key $Key We create a new completely random 32 byte (256-bit) array to use as a key with AES encryption. We get text input from the user, stored as a SecureString object which is automatically protected in memory by DPAPI encryption. We then convert it from a SecureString object to just cipher text and we provide that 32 byte key. We end up with Base64 encoded cipher text like this:

76492d1116743f0423413b16050a5345MgB8ADIAaQA5ADkARgBKAHYAZABDAHAAQQB1ADgARgBrAFUAYgAwAEgAZgBLAFEAPQA9AHwANAA1ADAAY

wA3AGMANgAzADEAMwBmAGIAMwBhADIAMAAwADkANQA1AGQANAA3ADAAZAA5ADYAYQBlADgAOABhADIAOABmADgAYgA0AGMAZgAxADQAOAAyADkANg

AyADIANwBiADAAMQBlADcAZgBhADEAZQBkAGEAMQBmAGIANwBiAGIAOAA5ADIAYQA0ADMAYQBmADQAOQBlAGMAZQA1AGQAYQA0AGEAOQBlAGYAZAB

hAGUAMgA4ADQAMwA5ADAA

Now, we can save that to a file AND save our $Key variable to a file for use on the same system or a different system.

# Save the Key to a file

Out-File -FilePath "C:\Scripts\AESKey" -InputObject $Key

# Save the encrypted text to a file

Out-File -FilePath "C:\Scripts\TopSecret.txt" -InputObject $AESTextYou can move those files to another computer, for another user even, and they can be used in this way.

# Import my AES Key

$Key = Get-Content "C:\Scripts\AESKey"

# Import my encrypted text

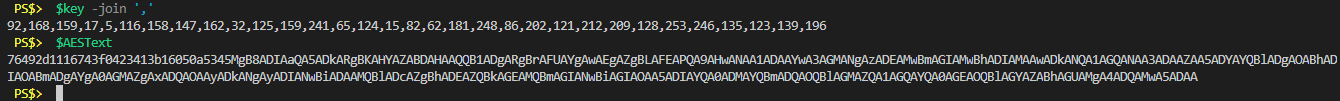

$AESText = Get-Content "C:\Scripts\TopSecret.txt"Here’s a picture of what their values look like (common joined the key for easier viewing)

We can use that AES Key to convert our encrypted text back in to a SecureString object.

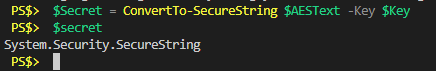

# Convert the encrypted text in to a SecureString object

$Secret = ConvertTo-SecureString $AESText -Key $Key

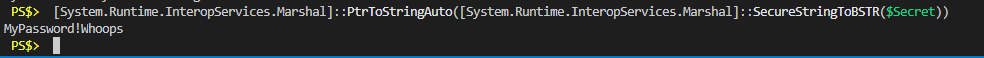

That SecureString object is now protected in memory with DPAPI encryption again. To convert it to plain text we have to use some .NET methods. Here’s a rather long one-liner that accomplishes this.

# Convert a SecureString object to plain text

[System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::PtrToStringAuto([System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::SecureStringToBSTR($Secret))

There it is. That’s how you can use a random key to convert SecureString objects to AES protected text, transport them somewhere, and decrypt them. But, you can’t just leave that AES key laying around anywhere. That would be like locking all of your valuables up in your house behind the strongest locks you could get, and then leaving the key laying under the doormat. We don’t protect our password managers like this, why should it be any different for credentials in Powershell?

One thing I never liked about the above method was that you really need to save that AES key somewhere because it’s impossible to remember or produce again. One day while tumbling through Github I found a mobule by greytabby called PSPasswordManager. What particularly caught my attention was the class definition within for “AESCipher.” Here it is straight from Github.

class AESCipher {

[byte[]] $secret_key

AESCipher() {}

[string] secure_string_to_plain($secure_string) {

$bstr = [System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::SecureStringToBSTR($secure_string)

$plain = [System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::PtrToStringBSTR($bstr)

[System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::ZeroFreeBSTR($bstr)

return $plain

}

[string] padding($key) {

# aes key length is defined 256bit

# padding key

if ($key.length -lt 32) {

$key = $key + "K" * (32 - $key.length)

}elseif ($key.length -gt 32) {

$key = $key.SubString(0, 32)

}

return $key

}

[void] input_secret_key() {

$input_string = Read-Host -Prompt "Enter your secret key" -AsSecureString

$input_plain = $this.secure_string_to_plain($input_string)

$enc = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8

$padded_key = $this.padding($input_plain)

$key = $enc.GetBytes($padded_key)

$this.secret_key = $key

}

[string] encrypt ($plain) {

# plainpassword to securestring

$secure_string = ConvertTo-SecureString -String $plain -AsPlaintext -Force

# securestring to encrypted text

$cipher = ConvertFrom-SecureString -SecureString $secure_string -key $this.secret_key

return $cipher

}

[string] decrypt ($cipher) {

# cipher text to secure string

$secure_string = ConvertTo-SecureString $cipher -key $this.secret_key

# secure string to plain text

$plain = $this.secure_string_to_plain($secure_string)

return $plain

}

}I observed that the intention was to provide a “secret key” or “master password” and then a 32 byte key would be derived from that and used to encrypt/decrypt the things inside the vault. As per usual, I got so focused on this that I failed to bring my head up and look around much at the bigger picture. I decided to just completely tax this class definition from greytabby and start working on the structure of my own password manager.

After a couple months of only sporadically working on this I hadn’t made much headway. A couple more class definitions, and some notes about desired functions, but I was finding myself busy with other things. Having a bit of a reputation around the shop as a Powershell nut I was asked one day to review a proposed solution provided by someone else. The request was to let some users do something on a server that requires administrative privilege, but not actually give them that privilege. The solution that was provided, via Powershell, was essentially to encrypt some admin credentials using a randomly generated AES key then create a script on the user’s computer that would know to retrieve the key file and cipher text from a restricted network share and then it would execute the tasks on the server as those credentials. While the logic was there, some of it was security through obscurity and ultimately it was just giving them admin credentials with extra steps. Anyone with access to the script file could see where the key file and encrypted text file were being store and go decrypt them at will if they like. It also meant that the keys to the castle would just be sitting on disk somewhere.

As I was calling these things out in my review I thought of the above class definition for an “AESCipher” and I thought *“oh hey, we could just tell the users some master password that they store securely in a password manager, and then they’d use that when they run the script and it would decrypt the saved credentials. Again, this was just giving them admin credentials with extra steps.

There was a benefit from this though because it got me looking at this class definition again and looking at specifically how he managed to take a provided password and generate the same AES key each time.

In the class definition let’s focus on this.

[String] Padding($Key) {

# AES Key Length is defined 256bit

# Padding Key

if ($Key.Length -lt 32) {

$Key = $Key + "K" * (32 - $Key.Length)

}

elseif ($Key.Length -gt 32) {

$Key = $Key.SubString(0, 32)

}

return $Key

}

[void] InputSecretKey() {

$InputString = Read-Host -Prompt "Enter your secret Key" -AsSecureString

$InputPlain = $this.SecureStringToPlain($InputString)

$Enc = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8

$PaddedKey = $this.Padding($InputPlain)

$Key = $Enc.GetBytes($PaddedKey)

$this.SecretKey = $Key

}Knowing that we want to end up with a 32 byte key the InputSecretKey() method leverages the Padding($Key) method to add extra bytes to the provided secret. If we use the secret “TopSecret” for example, that’s 9 characters, which is good for 9 bytes if we convert it. That leaves 23 bytes we still need. What greytabby did was just an if/elseif statement: If the resulting key length from our master password is less than 32 bytes then add the byte value for “K” X amount of times. If It’s greater than 32 characters then only take the first 32 characters. The Byte array for “TopSecret” would look like this:

84,111,112,83,101,99,114,101,116,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75,75Notice all those “75”s? That’s the UTF8 byte value for a capitol “K”. I had flashbacks to working on my Natural Language Password script where I was looking to make sure I used the best random number generator available to me. In that process I found myself on this article from Matt Graeber that went in to pretty good detail about the differences between the Powershell cmdlet Get-Random and the .NET method RNGCryptoServiceProvider. The part that stuck in my brain was “entropy.” I didn’t feel good about creating an AES key based on a password that was always going to have a bunch of repetitive byte values. Armed with even just that it would be significantly easier to brute force the original key.

I started thinking more about how to better derive 32 bytes of random key values given a provided string. Unfortunately my scratch .ps1 file where I was testing different ideas is lost, but I’ll try to summarize so you can laugh at me.

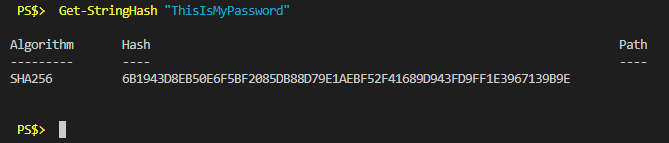

Knowing I didn’t want to just add some consistent character to the string to hydrate a 32 byte array full of values I thought about some different options. I could double a given master password, or triple it, or whatever until it reached 32 bytes. There would be too obvious of a pattern in that. Oh, well, what do most authentication systems do? They hash the password. Surely Powershell must have a way to generate hashes of strings. As it turns out, it does not. There’s a Get-FileHash cmdlet, but as the name implies it’s for files. So I wrote this function to create hashes of strings.

Function Get-StringHash {

[Cmdletbinding()]

Param (

[Parameter(Mandatory = $true, Position = 0, ValueFromPipeline = $true)]

[String]$InputString,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false, Position = 2)]

[ValidateSet("SHA1","SHA256","SHA384","SHA512","MACTripleDES","MD5","RIPEMD160")]

[String]$Algorithm = "SHA256"

)

Process {

$Stream = [IO.MemoryStream]::New([byte[]][char[]]$InputString)

$Output = Get-FileHash -InputStream $Stream -Algorithm $Algorithm

$Stream.Dispose()

}

End {

$Output

}

}The use would look something like this.

A SHA256 hash results in a 64-byte output string, every time, and it’s completely unique. Awesome, I’d solved it. But, I only needed 32 bytes so I decided to just use every other byte for a total of 32.

Pretty soon I had a function worked up to convert a supplied password (passphrase) in to a unique AES Key. But then that word started nagging me again. Entropy. Had I really created a function that would generate a key as unique as a randomly generated one? I decided that I should modify Matt Graeber’s work from the Powershell Magazine article and measure the entropy of randomly generated 32 byte arrays, and then my password derived byte arrays.

Again, the Powershell work I wrote to test this is gone and I don’t really feel like recreating it, but the gist is: I would use my Natural Language Password script to generate 1000 unique passphrases and I would generate 1000 unique randomly generated 32 byte keys. I would then compare the entropy of each method’s 1000 iterations and average the results. A random key was generating an average entropy calculation of 4.88. My function was somewhere around 3.42. I realized that hashstrings don’t include every possible character and therefore couldn’t produce every possible byte value. I tinkered with multiplication, Get-Random seeding, other hash algorithms, and a couple of other things but the highest I got my entropy number to was something like 3.62. I wasn’t happy. I searched the internet for something like “AES Key password based” and one of the results was “PBKDF2” or “Password Based Key Derivation Function.”

There I go again, not seeing the forest for the trees. Of course something like PBKDF2 exists, how else would be get unique keys for password managers, VPN connections, etc. A little bit of searching later and I had found a .NET method for leveraging PBKDF2 and when I tested it for entropy I was getting 4.88, just like the randomly generated keys.

Focusing on the idea of an end user providing a master password, and turning that in to a unique 32 byte key, I set to work on a function for accomplishing this. Here’s the final product so we can go through it.

Function ConvertTo-AESKey {

[cmdletbinding()]

Param (

[Parameter(Mandatory = $true, Position = 0)]

[System.Security.SecureString]$SecureStringInput,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false)]

[String]$Salt = '|½ÁôøwÚ♀å>~I©k◄=ýñíî',

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false)]

[Int32]$Iterations = 1000,

[Parameter(Mandatory = $false)]

[Switch]$ByteArray

)

Begin {

# Create a byte array from Salt string

$SaltBytes = ConvertTo-Bytes -InputString $Salt -Encoding UTF8

}

Process {

# Temporarily plaintext our SecureString password input. There's really no way around this.

$Password = ConvertFrom-SecureStringToPlainText $SecureStringInput

# Create our PBKDF2 object and instantiate it with the necessary values

$PBKDF2 = New-Object Security.Cryptography.Rfc2898DeriveBytes -ArgumentList @($Password, $SaltBytes, $Iterations, 'SHA256')

# Generate our AES Key

$Key = $PBKDF2.GetBytes(32)

# If the ByteArray switch is provided, return a plaintext byte array, otherwise turn our AES key in to a SecureString object

If ($ByteArray) {

$KeyOutput = $Key

} Else {

# Convert the key bytes to a unicode string -> SecureString

$KeyBytesUnicode = ConvertFrom-Bytes -InputBytes $Key -Encoding Unicode

$KeyAsSecureString = ConvertTo-SecureString -String $keyBytesUnicode -AsPlainText -Force

$KeyOutput = $KeyAsSecureString

}

}

End {

return $KeyOutput

}

}With this function, if you provide the same password, you’ll get the same very unique, seemingly random, 32 byte key out of it. It can be reproduced on any computer with this same function.

The information for the .NET “Rfc2898DeriveBytes” method wasn’t hard to find, and all of the other articles surrounding PBKDF2 seemed to make sense. You need to provide a clear text password, a salt (in byte form), the number of iterations (1000 is standard) and the hashing algorithm. You can see in the above code I provided the salt statically. While this is exposed, it’s mostly to prevent against rainbow table attacks so this is seen as acceptable. There are a couple of help functions called out in here that I wrote along with this:

ConvertTo-Bytes ConvertFrom-Bytes ConvertFrom-SecureStringToPlainText

These just make it easier to read what’s happening but they’re all essentially using some .NET class in the background.

For security sake the derived key is then converted to a SecureString object using the standard DPAPI encryption and then returned.

As an example, if I was to feed the password “password” in to the above function the resulting byte values would be

58,17,32,1,253,255,156,186,174,118,20,201,237,59,75,81,38,137,247,12,31,34,162,127,17,116,183,247,85,27,246,10

I now had a function that would deal with collecting the master password from the user, and a function for converting that in to a unique AES Key using PBKDF2. As well as some helper functions. Now it’s time to encrypt some stuff.

I’ve covered how to protect string data with SecureString objects and AES encryption, and that’s exactly how I started this. I’d generate a unique key using my ConvertTo-AESKey function and then I would convert the supplied unprotected text to a SecureString object, convert it from a SecureString object with my AES Key and then output the resulting cipher text.

I did notice a bit of a pattern though when looking at some example text. Consider the following code and assume the $Key variable has a key in it already

$Words = @("test","test2","stuff","things")

Function Protect {

Param (

$InputObject

)

$SecureString = ConvertTo-SecureString $InputObject -AsPlainText -Force

$CipherText = ConvertFrom-SecureString $SecureString -Key $Key

$CipherText

}

$Words | %{

Protect $_

}The output text looks like this

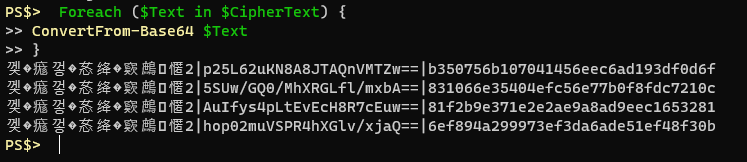

I’ve highlighted some repeating text observed at the beginning of each example. I tried to find more information about how exactly ConvertFrom-SecureString operates with regards to AES encryption but I couldn’t find much out there. The output text is all base64 encoded, and decoding it offers only a little extra info.

Loading the cipher text in to an array called $CipherText and doing a foreach loop on the array with a quick and dirty ConvertFrom-Base64 function you can see there’s a bit of a pattern. Some bytes of indiscernible value, a pipe, another Base64 string, a pipe and likely our encrypted text. No matter what I encrypt the first string of bytes seems to be the same. The Base64 string in the middle changes every time, even if you’re encrypting the same plain text with the same AES key. I’m thinking this is the initialization vector that ConvertFrom-SecureString uses with each iteration. Then the last string after the pipe must be our encrypted data.

In my searches though for how to properly leverage AES encryption on strings in Powershell I ran across this blog by Richard Ulfvin. He did a really nice job of going through how to use the .NET classes to protect strings with AES encryption.

I quickly refactored my current method to use what he shared and found that the returned cipher text is exactly what I dictated be output: the first 16 bytes were the initialization vector, followed by my encrypted data.

Putting together Richard’s method and adding a small function to handle the invocation of the .NET AES Crypto provider I ended up with this.

Function ConvertTo-AESCipherText {

<#

.Synopsis

Convert input string to AES encrypted cipher text

#>

[cmdletbinding()]

param(

[Parameter(ValueFromPipeline = $true,Position = 0,Mandatory = $true)]

[string]$InputString,

[Parameter(Position = 1,Mandatory = $true)]

[Byte[]]$Key

)

Process {

$InitializationVector = [System.Byte[]]::new(16)

Get-RandomBytes -Bytes $InitializationVector

$AESCipher = Initialize-AESCipher -Key $Key

$AESCipher.IV = $InitializationVector

$ClearTextBytes = ConvertTo-Bytes -InputString $InputString -Encoding UTF8

$Encryptor = $AESCipher.CreateEncryptor()

$EncryptedBytes = $Encryptor.TransformFinalBlock($ClearTextBytes, 0, $ClearTextBytes.Length)

[byte[]]$FullData = $AESCipher.IV + $EncryptedBytes

$ConvertedString = [System.Convert]::ToBase64String($FullData)

}

End {

$AESCipher.Dispose()

return $ConvertedString

}

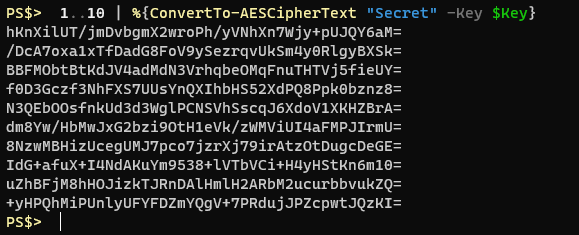

}Example output from that function would look like this.

Note that encrypting the exact same string, with the same key, 10 times produces completely different cipher text. This is what true encryption should look like. Notice it’s also a bit more succinct than the ConvertFrom-SecureString method since it doesn’t have that mystery text at the beginning.

At this point I knew I wanted to be able to collect a master password from the user, derive a unique key from that, store it somewhere within the session for recurring use, and then encrypt and decrypt strings with it. It might also be nice to be able to export the unique key to a file and similarly import it from a file. This would allow you to provide a super long, complex, hard to memorize password, and still save the resulting key somewhere. This would be very similar in function to just randomly generating an AES key and saving the key to a file somewhere.

It would be nice to be able to check if the master password has been set. Remove it if needed, and also set it to a desired master password. For public facing functions that sets me up with:

Export-MasterPassword

Import-MasterPassword

Get-MasterPassword

Set-MasterPassword

Protect-String

Remove-MasterPassword

Unprotect-String

On the private side of things however there’s a quite a few more things at play. I’ll list them and then talk about a few of them:

Clear-AESMPVariable

ConvertFrom-AESCipherText

ConvertFrom-Bytes

ConvertFrom-SecureStringToPlainText

ConvertTo-AESCipherText

ConvertTo-AESKey

ConvertTo-Bytes

Get-AESMPVariable

Get-DPAPIIdentity

Get-RandomBytes

Initialize-AESCipher

New-CipherObject

Set-AESMPVariable

Set, Get and Clear AESMPVariable are all about storing the key in a global session variable. I was picturing myself importing a CSV to a variable and then encrypting certain properties from that CSV before writing it back out to a CSV file. I wouldn’t want to have to supply the same master password every time I performed this operation. The only thing I could think of so far was a global scope session variable. You can manually protect the data by running the “Remove-MasterPassword” function which will clear out the variable. In the future I may find a way to add a time-based limit on it, but my efforts towards that so far have been failures.

ConvertFrom-SecureStringToPlainText, while horribly named, is straight forward. It shows you the plaintext from a SecureString object by decrypting DPAPI protection.

A lot of the other functions are just pretty wrappers on a terse call to a .NET class. ConvertTo and ConvertFrom AESCipherText are all about performing that encryption and decryption operation described above using the supplied key from the master password.

Shortly after proving the function of most of my functions I had the thought that maybe, just maybe, I might (or someone else might) want to use the DPAPI encryption rather than AES. I decided that I would format my protected string output to conform to that of an object. The object would have two properties: Encryption type, and cipher text. The Encryption type would either be DPAPI or AES, and then the cipher text property would hold the encrypted text. Time for a class definition.

Class CipherObject {

[String] $Encryption

[String] $CipherText

hidden[String] $DPAPIIdentity

CipherObject ([String]$Encryption, [String]$CipherText) {

$this.Encryption = $Encryption

$this.CipherText = $CipherText

$this.DPAPIIdentity = $null

}

}This leads me in to talking about the Get-DPAPIIdentity function. Since DPAPI’s key is based on the user and the system I thought it might be handy to add that information to the output. That way if you attempt to decrypt DPAPI protected strings on another system, or as a different user, the error message could say who originally protected it.

If you attempt to decrypt AES protected text you’ll just get an error message stating that the key was incorrect and it will wipe out the currently saved master password.

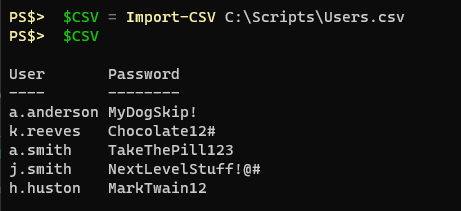

Let’s say we had a CSV file with some sensitive information in it, like usernames and passwords, and the CSV looked like this.

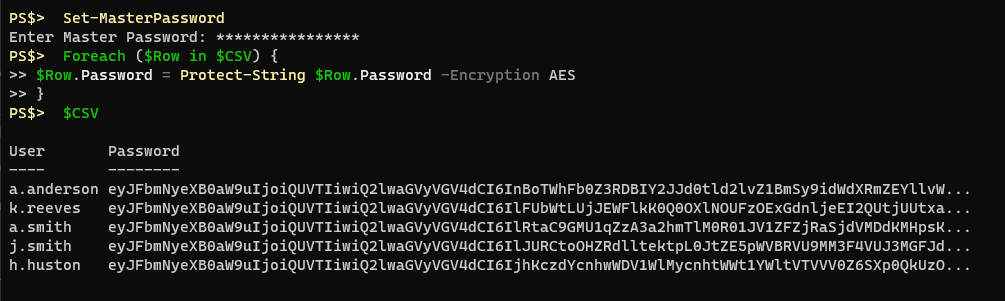

With the ProtectStrings module imported I can set my master password I want to use for encryption/decryption and then I can loop through this CSV and protect the sensitive information.

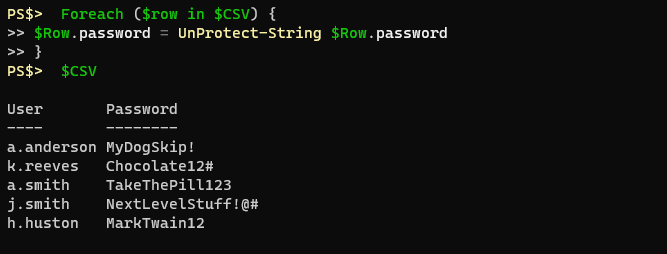

Then I can Export-CSV from that variable and safely write that information to disk. I can transport it to other computers, or other accounts, and when I reach my destination I can load the ProtectStrings module, set my master password, import the CSV, and loop through to decrypt the strings.

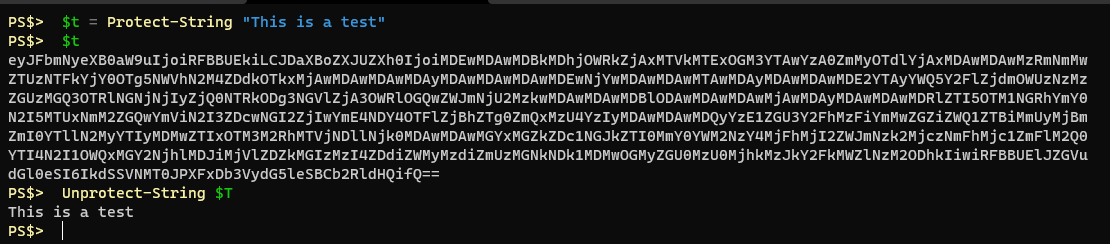

Here’s an example using the DPAPI encryption, which is currently the default if you don’t specify.

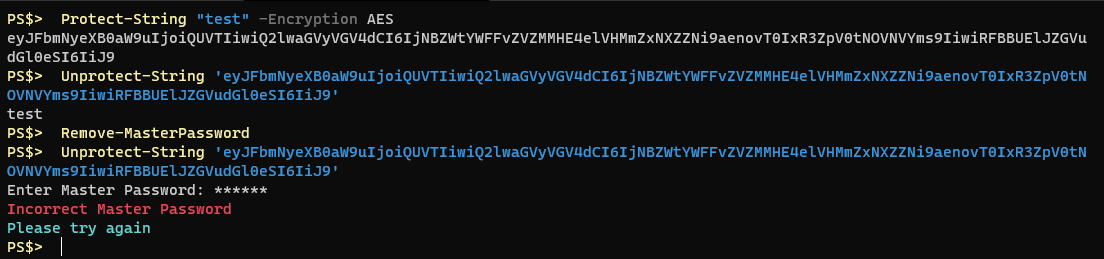

Here, I protect a string using AES encryption, then I clear the master password from the session and attempt to decrypt the same string again. I intentionally provide an incorrect master password, resulting in an error

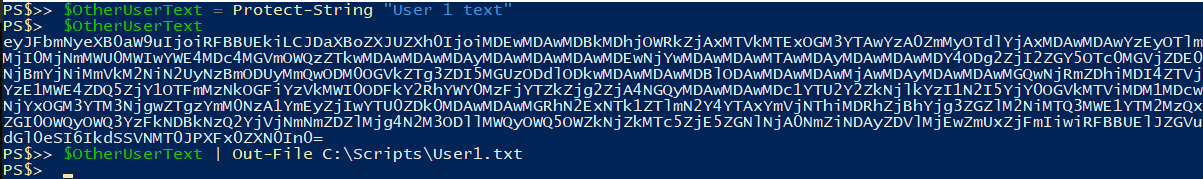

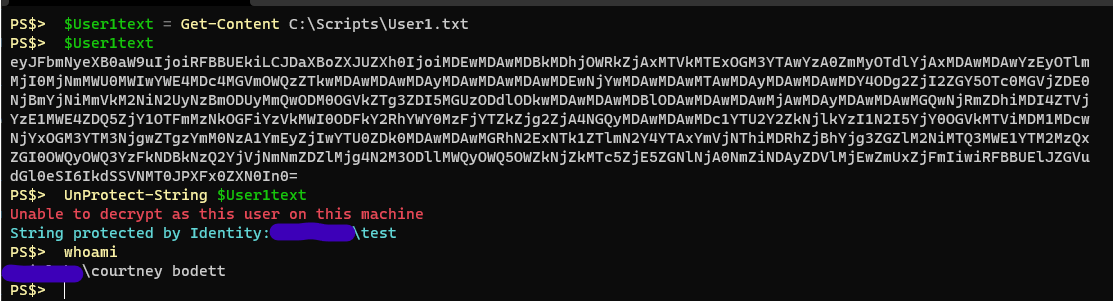

If I use a different user account, or different PC, to protect a string using the default DPAPI encryption and then save that output to a file and transfer it to another user you will see that the decryption fails because I am not the same user.

Powershell is still fun and I still learn something new every day. Ultimately this module may not be very practical or have a lot of use, but it was a good exercise in writing functions and writing modules.

It’s not currently published anywhere as of writing this. I’m still using it internally and I have a specific project in mind where it could be helpful. This will help me iron out the kinks and eventually I’ll publish it to my repository on Github.

I’m not much of a cryptographer so if you see any glaring flaws please feel free to email me. Or if you have questions you may do the same.

Be good everyone, or be good at it.

Homelab Homelab / ˈhoʊm.læb / noun A personal IT environment where individuals can experiment, learn and test various technologies. A server (or multipl...

I remember years ago when I first made a bootable Kali thumb drive (‘BackTrack’ back then) with encrypted peristence there was an option to create a sort of ...

Natural Language Passphrases Previously I talked about making small modules as an excuse to practice making tools and focus on making something that works we...

Size Doesn’t Matter When I made my first PowerShell module it was mostly an experiment to see if I could understand how they worked. It was simply tools.psm...

The more time I spend living in the CLI the more I appreciate learning and adopting shorthand for operations. In Powershell the aliases for Where-Object and...

I got the opportunity this week to attend the 2024 Powershell Summit in Bellevue Washington. If you have an opportunity to go to this, whether you’re brand ...

SecretManagement module is a Powershell module intended to make it easier to store and retrieve secrets. The secrets are stored in SecretManagement extens...

With more and more people working remotely there’s been a huge uptick in VPN usage. A lot of organizations have had to completely rethink some of their prev...

Hi all. Just wanted to provide a brief status update. It’s been a while since my last post and while I have been busy, and making frequent use of Powershel...

Getting GPS Coordinates From A Windows Machine Since 2020 a lot of organizations have ended up with a more distributed workforce than they previously had. T...

I was writing a new function today. Oddly enough I was actually re-writing a function today and hadn’t realized it. Let me explain. Story Time About a hal...

I’ve had an itch lately to do something with AES encryption in Powershell. I’ve tossed around the idea of building a password manager in Powershell, but I g...

“If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail” - Abraham Maslow. I use a variation of this quote a lot, and I typically use it in jest, but it’s...

Introduction I’ve had some exposure to Microsoft Defender here and there, but I was in a class with Microsoft recently where they were going over some more f...

In my previous post I explained a bit about some of my justifications for logging in Powershell. My interest in logging has continued since then and I spent...

Everyone has a different use for Powershell. Some people use it for daily administrative tasks at work. Some people are hard at work developing Powershell m...

Early on when I first started using Powershell I was dealing with some firewall logs from a perimeter firewall. They were exported from a SIEM in CSV format...

One of the tools I feel like I’ve been using for years is Netstat. It exists in both Linux and Windows (with some differences) and has similar syntax. It’s ...

A coworker from a neighboring department had an interesting request one day. They wanted a scheduled task to run on a server. Through whatever mechanism the ...

When I first started getting in to Powershell I was working in an IT Security position and was sifting through a lot of “noise” in the SIEM alerts. The main...

“Hello World” and all that. What started as a small conversation turned in to an Idea that I couldn’t shake: I wanted a blog. But I didn’t want a WordPress...